A mainstay of U.S. foreign policy in the Post-War era has been the deployment of hundreds of thousands of military personnel to countries around the globe. Since 1950, almost a quarter of U.S. troops were deployed abroad in an average year (Kane 2006). This trend evolved from World War II, as the United States began to acquire overseas bases. Many temporary wartime deployments became permanent presences codified in treaties between the U.S. and host countries during the Cold War. Despite their importance to U.S. foreign policy and world politics, we are just beginning to understand many of the non-security dimensions of these deployments, and the social, economic, and political effects they have on their host environments.

A mainstay of U.S. foreign policy in the Post-War era has been the deployment of hundreds of thousands of military personnel to countries around the globe. Since 1950, almost a quarter of U.S. troops were deployed abroad in an average year (Kane 2006). This trend evolved from World War II, as the United States began to acquire overseas bases. Many temporary wartime deployments became permanent presences codified in treaties between the U.S. and host countries during the Cold War. Despite their importance to U.S. foreign policy and world politics, we are just beginning to understand many of the non-security dimensions of these deployments, and the social, economic, and political effects they have on their host environments.

Many host-state residents are more likely to encounter U.S. military personnel than other U.S. government actors. This means that their perceptions regarding the United States, its government, and people may be heavily influenced by the nature of these interactions. U.S. military personnel are thus serving an underappreciated, and often unintentional, role as public diplomats. Our research helps us understand this role and its policy implications.

“They Were Elated to Have Us There”

To understand the microfoundations of public opinion formation regarding the U.S. and its overseas military presence, we needed individual-level data. We began by surveying 1,000 people in each of the following countries: Australia, Belgium, Germany, Italy, Japan, Kuwait, the Netherlands, the Philippines, Poland, Portugal, South Korea, Spain, Turkey, and the United Kingdom. This yielded a full sample of about 14,000 individuals. We chose this set of countries because they have either a sizeable post-Cold War U.S. military presence or smaller recent but politically salient peacetime deployments, and the survey could be locally administered. Respondents were a nationally representative sample based on gender, age (over 18), and income. We asked each respondent 50 questions related to their demographic characteristics, the U.S. military deployments in their country, and their views on several local and global issues.

We also traveled to two Latin American countries, Panama and Peru, to conduct in-person interviews with U.S. government and military officials, local government officials, and local civil-society actors. These interviews allowed us to better understand the theoretical foundations of the processes through which opinions are formed. This afforded insights into the thoughts of the populations—“When Peruvians think about the U.S. military they think about muscular men with tattoos waving around the flag and yelling about liberty and democracy,” said a young Peruvian journalist—as well as into some of the experiences of members of the military interacting with locals—when the USNS Comfort carried out a humanitarian mission in Colombia in 2007, “they were elated to have us there,” noted a U.S. Naval Commander.

Military Personnel as Public Diplomats

Given the relative lack of research on local perceptions of U.S. troop deployments, an initial subject of interest was the local populations’ perception of U.S. troops and how that may relate to perceptions of the U.S. government and the U.S. population more broadly. As shown by Figure 1, survey respondents expressed mostly positive or neutral attitudes regarding the presence of the U.S. troops in their country, while attitudes were generally more positive toward the American people and more negative toward the U.S. government.

Figure 1. Attitudes toward troop presence

Of course, we expected that these views would be dependent on how individuals come into contact with the military, their social networks’ interaction with military personnel, and any economic benefits they may receive from U.S. military deployments.

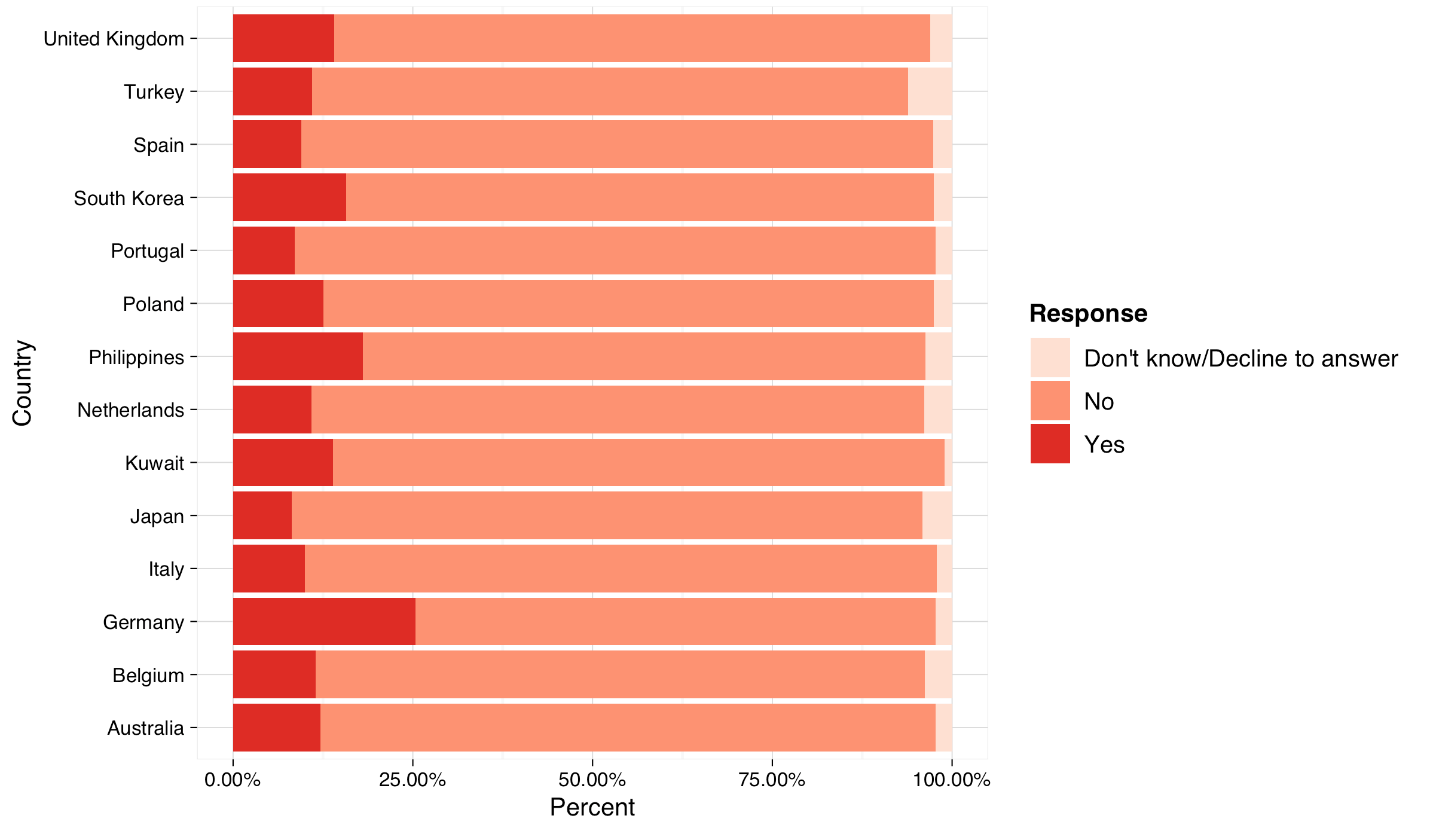

Figure 2. Personal contact with US personnel

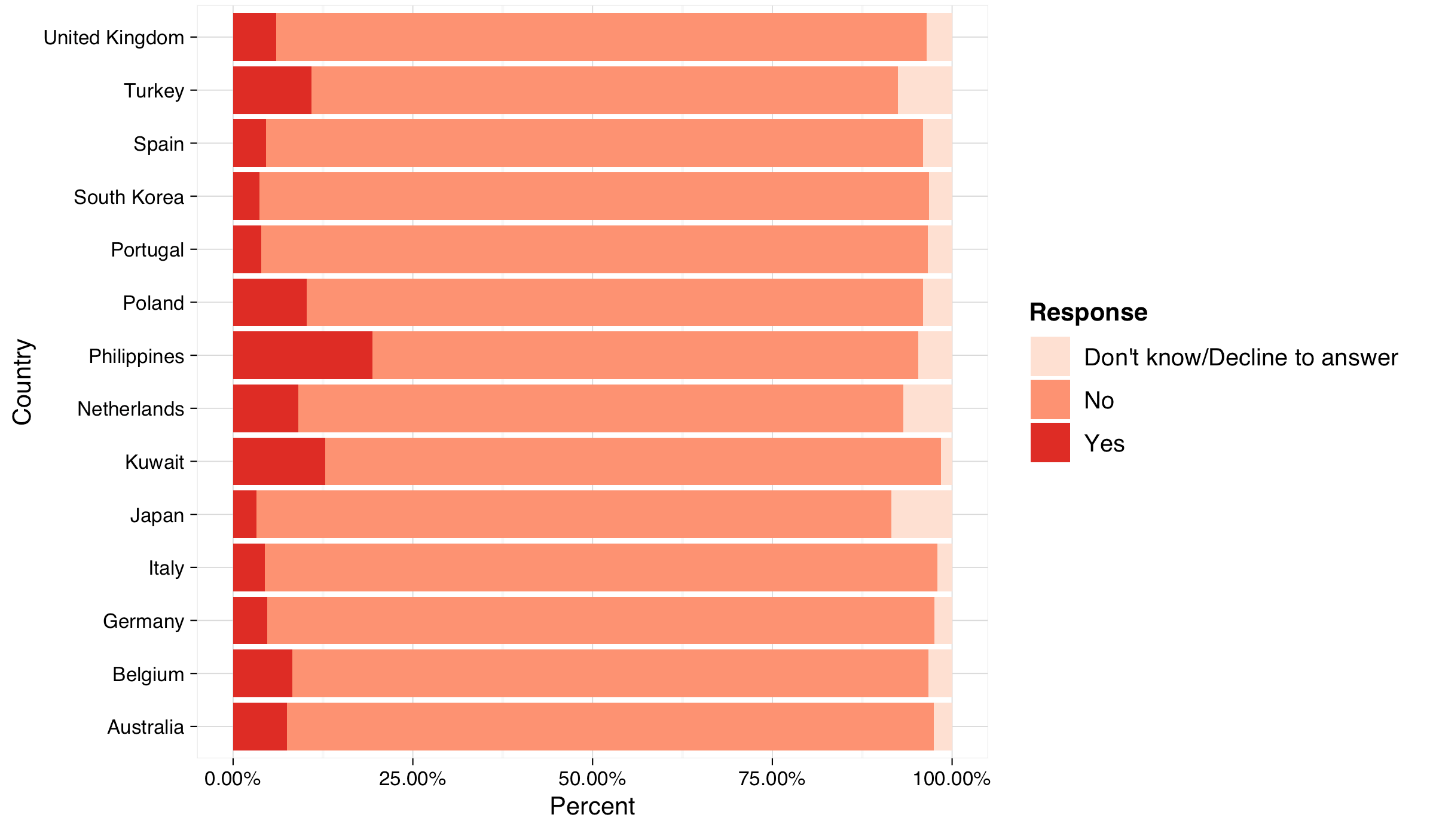

As shown by Figures 2 and 3, the percentage of people who report personal contact with or economic benefits from U.S. troops is a small fraction of the population—roughly 13 percent of the total sample reported direct contact with U.S. personnel and 8 percent reported direct economic benefits from the presence. Yet, our initial statistical tests indicate that there is a positive relationship between the above factors and individuals’ perceptions of the U.S. military personnel, government, and people (Allen, et. al. 2019). This supports the idea that U.S. military personnel engage in public diplomacy during peacetime deployments and that these encounters contribute to positive perceptions of the U.S. in host states.

Figure 3. Receive personal economic benefit from US presence

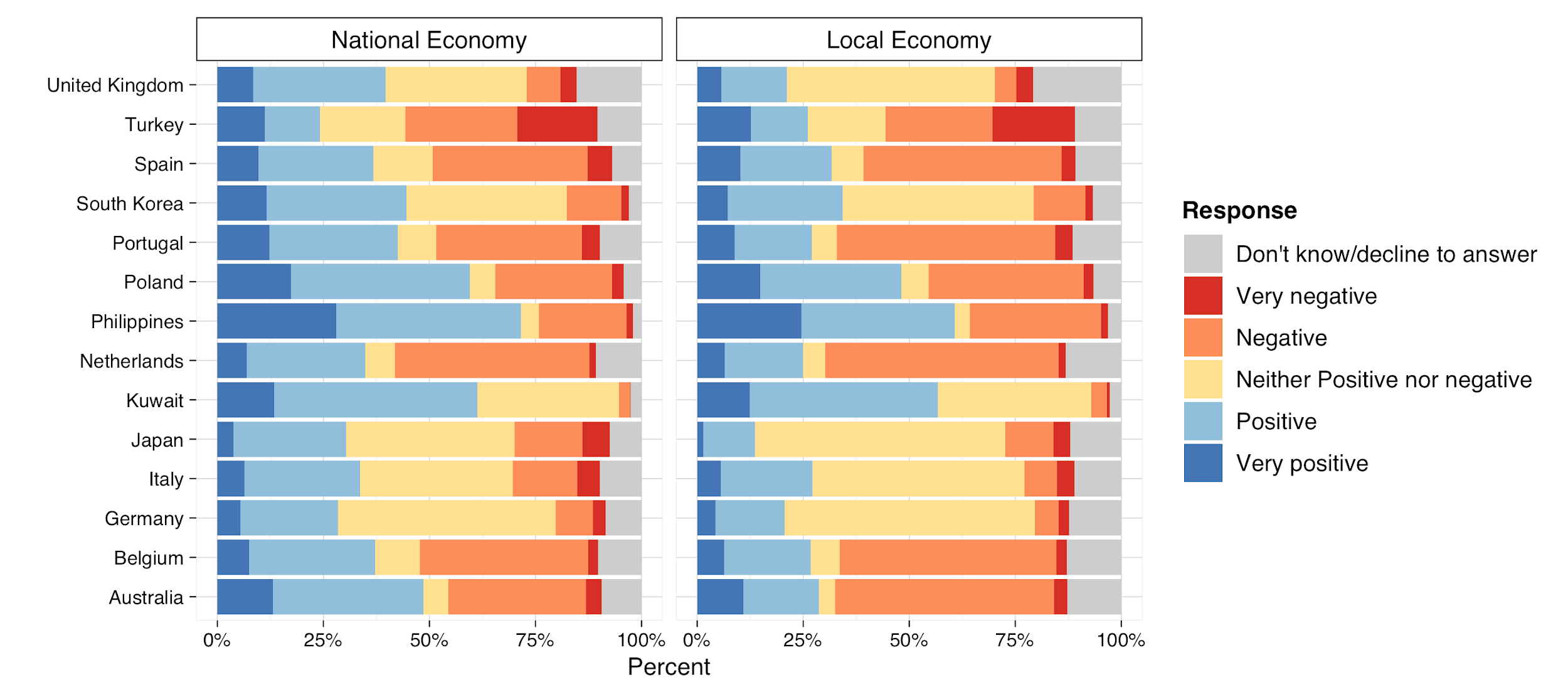

A second series of questions asked whether people thought troops had a positive impact on their local or national economy. Interestingly, in every country, people were much more likely to see a positive national-level effect than a local one, as shown by Figure 4. Of note, positive views of the U.S. military’s economic effects tend to be higher in the Philippines, Kuwait, and Poland. Alternatively, they are lower in Germany, Italy, and Japan—some of the original post-War host states. Excepting the Philippines, these patterns may correspond with how recently U.S. forces arrived. Longer-standing presences are perceived as having a more negative or neutral effect on national economies, while newer deployments are perceived as an economic boon.

Figure 4. Attitudes of troop impact on economy

Beyond Financial Transactions: Forging Relationships in a Complex Setting

This preliminary evidence provides some insights into how people in other countries perceive the U.S. and its military deployments, as well as how the perceived benefits and costs of those deployments affect those views. Both direct and indirect economic benefits can bolster positive views of the U.S. In addition, there is evidence suggesting that military personnel play an important role in public diplomacy for the United States in peacetime deployment contexts. Our results indicate that simply interacting with members of the U.S. military can, on average, cultivate more positive views of the U.S. and its institutions.

The nature of the interaction can of course influence these effects. We note, for example, that we examine only non-invasion deployments. Local populations in host countries are highly sophisticated in distinguishing between the U.S. military, government, and population. They react in distinct and complex ways to different interactions with the U.S. military, such as financial transactions and face-to-face contact with U.S. military personnel. Moving forward in our research, we will continue to distinguish between different forms of interaction as well as dig deeper into both the costs and benefits of deployments for host populations How and why people react to the U.S. military presence is multifaceted; personnel abroad face both support and backlash in the same communities in which they are stationed. Understanding the underlying causes of people’s attitudes toward a U.S. presence is pivotal for the success of U.S. foreign policy and the countries that host U.S. personnel.

Associated Reading

Allen, Michael A., and Michael E. Flynn. 2013. Putting Our Best Boots Forward: US Military Deployments and Host-Country Crime. Conflict Management and Peace Science. 30(3): 263-285.

Allen, Michael A., Michael E. Flynn, Carla Martinez Machain, and Andrew Stravers. 2019. Outside the Wire: US Military Deployments and Public Opinion in Host States. SSRN.

Flynn, Michael E., Carla Martinez Machain, and Alissandra Stoyan. Forthcoming. The Effect of U.S. Development-Oriented Troop Deployments on Public Opinion in Peru. International Studies Quarterly.

Jones, Garret, and Timothy Kane. 2012. US Troops and Foreign Economic Growth. Defence and Peace Economics. 23(3): 225-249.

Kane, Tim. 2006. Global U.S. Troop Deployment, 1950-2005. Heritage Foundation. Report CDA06-02., May 24.

Stravers, Andrew, and Dana El Kurd. Forthcoming. Strategic Autocracy: American Military Forces and Regime Type. Journal of Global Security Studies.

Biography

Michael Allen is an Associate Professor in the School of Public Service at Boise State University. His research on the effect of US military personnel abroad is published in International Interactions, Foreign Policy Analysis, and Conflict Management and Peace Science.

Michael Allen is an Associate Professor in the School of Public Service at Boise State University. His research on the effect of US military personnel abroad is published in International Interactions, Foreign Policy Analysis, and Conflict Management and Peace Science.

Michael E. Flynn is an Associate Professor in the Political Science Department at Kansas State University. His work on military personnel abroad is in Conflict Management and Peace Science, Foreign Policy Analysis, International Studies Quarterly, and International Interactions.

Michael E. Flynn is an Associate Professor in the Political Science Department at Kansas State University. His work on military personnel abroad is in Conflict Management and Peace Science, Foreign Policy Analysis, International Studies Quarterly, and International Interactions.

Carla Martinez Machain is an Associate Professor in the Political Science Department at Kansas State University, the President of the International Studies Association Midwest Region, and an editor of International Interactions. Her work on military personnel has appeared in International Studies Quarterly, Journal of Conflict Resolution, and Armed Forces and Society.

Carla Martinez Machain is an Associate Professor in the Political Science Department at Kansas State University, the President of the International Studies Association Midwest Region, and an editor of International Interactions. Her work on military personnel has appeared in International Studies Quarterly, Journal of Conflict Resolution, and Armed Forces and Society.

Andrew Stravers is a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow in the Government Department at the University of Texas in Austin. He has published about military personnel abroad in Conflict Management and Peace Science and has work forthcoming in Journal of Global Security Studies.

Andrew Stravers is a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow in the Government Department at the University of Texas in Austin. He has published about military personnel abroad in Conflict Management and Peace Science and has work forthcoming in Journal of Global Security Studies.

Associated Minerva Project

The Political, Economic, and Social Effects of the United States’ Overseas Military Presence

Managing Service Agency

Army Research Office

Nota Bene

Content appearing from Minerva-funded researchers—be it the sharing of their scientific findings or the Owl in the Olive Tree blogs posts—does not constitute Department of Defense policy or endorsement by the Department of Defense.